This isn’t the end of the Defending Disney series. I’m still writing that. But, since that isn’t the only part of pop-culture that interests me, I wanted to branch out and start another series for another often maligned genre: horror.

If anything, the evils of horror are even more ubiquitous than Disney’s controversies. Feminists point out the fetishized female violence and damsels in distress. Religious people dislike the use of the supernatural, demons, and the occult. Gun rights activists blame horror movies for violent crime. Progressives criticize their portrayal of sexuality, because have-sex-and-die isn’t exactly progressive social policy (although some people approve). And, in general, horror fans are considered weird, awkward, creepy, and generally stereotyped as the kind of people you don’t want around your kids.

I’ve been told before that I don’t seem like a horror fan because I am “too calm” and “too bookish” –and I briefly worked for a horror magazine. This one.

Here, however, I am saying “discuss” instead of “defend”, because I find it more interesting to run these stories through social and theoretical schools of criticism than spend my time talking about all the controversies surrounding every horror film and work of literature. Also, I may not necessarily defend a film or book, but that doesn’t mean that I do not think that we can understand these stories in their social contexts.

So, you don’t have to like it. We’re just going to try and understand it and look at the tropes through different cultural lenses. And, since horror is a pretty broad subject, I’ll be taking varied selections, from Universal classic monsters, to silent scares, slashers, “goreno”, Asian extreme, cult horror, exploitation, arthouse, and cross-genre blends.

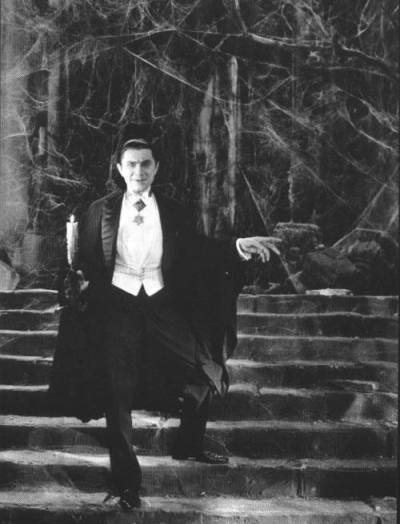

And, who best to start off a discussion of horror than the man who gave us one of the most classic horror movies of all time, 1931’s Dracula, by Tod Browning, starring horror legend, Bela Lugosi.

This film really needs no introduction, as Lugosi’s performance has become so legendary that I would bet if you were to mimic Dracula right now, you would mimic Lugosi. He’s the one who have us that awesome slicked-back hair, the way he swishes that opera cape, and his eerie line delivery. Cinema legend has it that the line delivery was due to Lugosi, who was native Hungarian, not being fully fluent in English. In fact, Lugosi was so associated with this role that he was buried in his Dracula costume. And yet, although this movie is so famous that until recently every other vampire movie was a footnote to this version, I find that not a lot of modern audiences have seen it.

Maybe this is because the movie is from the 1930s, and a lot of people seem to feel a disconnect with Old Hollywood acting these days, as well as the old-timey special effects and, well, it’s in black and white. Not to be condescending, but if we’re honest that is a real handicap for some viewers. I think this is a shame, since many people now associate old horror movies with bad horrors, like Robot Monster, and seem conditioned to laugh at the dialogue or special effects without giving the movie a real chance. However, this one actually really, really holds up.

And I’m not just saying that because I watched it for the first time as a child, at night, by the light of the fire, in my grandparents’ house in the woods, surrounded by cats, with wind and coyotes in the distance and… it was epic.

No, really, this movie still works. For one thing, the old film footage has been, as they say, lovingly restored, so the clarity of picture should not be a distraction. However, some of that old, warm feel from the film stock really, in my opinion, helps create the mood for a good horror experience. Part of what I love about horror is how weirdly cozy it is. It is cozy to be scared, to curl up with the popcorn and hot chocolate and everything. Halloween has always been a really nostalgic holiday for me, and the old footage and style really sets the tone for childhood Halloween experiences, at least for me. Something about it just screams candy-apples and community haunted houses.

But, aside from my personal feelings about the movie, the style is actually very affective. We may have seen the creepy castles, the cobwebs and shadows, the black capes, and bats before, but this is one of the earliest examples of the tropes. And, Browning’s direction really pushes the subtle eeriness that made these clichés affective in the first place. The scene when Dracula walks up the stairs has a really great moment when he is suddenly on the other side of thick cobwebs, having passed through them. This really drives home the otherworldly quality of Dracula’s character. There has always been a sort of tragedy to the vampire, cursed with immortality, as an eternal Other and monster, and here Browning highlights how much of an outsider Dracula is, that he does not belong in this world, even on the physical level.

Of course, the use of shadows, the gloomy lighting and angles, only further unsettle the viewer. But, it is actually the scenes of light that can be most unnerving. In one scene, Dracula attacks a sleeping woman. She has a light on. She is in her bed. The scene remains chilling because it strips away our security. If you aren’t safe in your own bed, in the light, then you’re always vulnerable.

But, it is the subject of the Other that really plays as a theme in the films I’m highlighting here. Dracula is an outsider because he is a monster. He’s frightening, a cold-blooded predator. When the ghost ship arrives, the entire crew slain by their vampire passenger, that is genuinely chilling. And yet, there is something enigmatic and interesting about Dracula. He’s sophisticated. He’s a gentleman. And, he is also a tragic character. In one scene, he speaks wistfully of death. Life and death, and what they mean to him, are what separates him. Life is blood, he says. Death is unattainable. Life, then, is the death of others, at the sacrifice of his own rest. Survival is the hunt, and the vampire is the everlasting predator.

Compare this to Tod Browning’s next film, 1932’s Freaks. After the success of Dracula, Browning wanted to make the greatest horror movie ever made. That next year, he released the story of a sideshow performer who is seduced by a trapeze artist. It starred actual sideshow artists, including Violet and Daisy Hilton, the conjoined twins, and other famous figures in the sideshow world. However, there is a twist. The sideshow characters are not the freaks, and the real monsters are the beautiful trapeze artist and her lover, who only trick the main character so as to con him out of his money.

It may not seem like an incredibly edgy movie. After all, today we are used to seeing the outcast and disfigured characters as the heroes and the handsome characters become villains. That’s basically the plot for Disney’s Beauty and the Beast, as well as movies like Mask, Edward Scissorhands, and The Elephant Man. However, in 1931, we lived in a different cultural landscape.

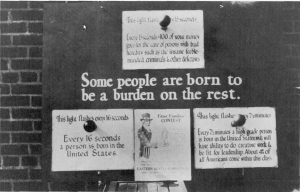

Film historians, meet pseudo-science. We’re probably going to see a lot of it. In the mid to late 1800s, a British scientist named Galton proposed a genetic theory. He called it eugenics. While it is basically the creationism of genetics today, back in the day it was all the rage. People had blood-line purity awards. People thought they could predict crime by the way someone’s eyes or head looked. It took a lot of ideas from another pseudo-science, phrenology, which held that examining the bumps in skulls would determine things like intelligence and criminal aptitude. You can see this played to chilling effect in Tarantino’s Django Unchained, when the sinister slave-owner, Candy, saws a skull in pieces to reveal the inside.

Of course, as seen in Django, this prejudice extended to race, and it would eventually inspire the Nazis. But, the idea that it was somehow unnatural to have mixed bloodlines or to be different from the norm is a much earlier and more wide-spread concept than the Nazi agenda. A great scene from Spielberg’s Lincoln really showcases this, with characters citing a very misinformed notion of “natural law”. And, for all intents and purposes, you can basically rest assured that 9 out of 10 times someone references “natural law” they are about to be a raging bigot –and also not understand what Natural Law means.

In the 1930s, it was not only edgy, it was downright counter-cultural to make a film like Freaks. This wasn’t just horror pushing the envelope. This was a socially conscious, progressive piece of cinema that pushed the boundaries of social acceptability, morality, and cinema itself. And Browning didn’t pull any punches. Audiences had seen sympathetic portrayals of disfigured characters in the past, what with Lon Caney playing both Erik from The Phantom of the Opera (1925) and Quasimodo from The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1923). But, these characters were created with make-up, and were also both based on pre-existing literature. Also, and I don’t know if many people realize this now, but the 1925 Phantom was considered pretty low-brow. It’s really not a very arty silent film, despite what people say about it these days, when comparing it to other, dumber versions.

The fact was, even though characters like Quasimodo and Erik existed, they were played by a mainstream movie star. In Browning’s film, however, no effects were used. The characters are real, 100%, with, of course, the exception being what happens to the villains at the end. But, I won’t spoil that for you. Furthermore, these are not villains. The sideshow performers are friendly, they have their own culture, they are loyal to one another, and they are portrayed as uniquely talented, not even as tragic. When bad things happen to them, you feel genuinely sorry, and not because they are victims due to their differences. No, you feel sorry because they are good people who are getting exploited.

Consider how even to this day we tend to portray characters as entirely defined by their “otherness”. A great example of this would be Glee. What is the defining attribute of Artie? Well, he’s in a wheelchair. What are his conflicts generally related to? His disability. Likewise, what is Kurt’s definite attribute other than his extreme gay… ness? But, this extends to other media. How often do we see characters whose only defining attribute is that they are black, or female, or blind, or gay, et cetera? These two-dimensional characters become tired clichés, like the Mammy, The Magic Black Man, The Underachieving Minority Student With a Dream, The Strong-Independent-Woman Who Don’t Need No Man, The Love Interest, Walking Boobs, The Inspirational Handicapped One, and The Sassy Gay Friend. Although sd seem to have made a breakthrough in portrayals of little people due to the talents of one Mr. Fantastic, Peter Dinklage, who proved to many viewers that when it comes to superstars, tall, dark, and handsome is really best two out of three.

Considering how ridiculously hard it is to get past this stereotyping problem in 2014, it’s amazing that Tod Browning wrote these characters in 1932. Hans and Frieda are a couple broken apart by the conniving femme fatale of a villainess, and it has nothing to do with the fact that they are little people. Likewise, the reportedly very upbeat Johnny Eck, who plays The Half-Boy, is an optimistic, happy-go-lucky kind of person. Aside from an ongoing gag about Violet and Daisy’s disagreements, they are also interesting characters, a little sassy, somewhat diva-ish, but interacting like any other pair of sisters. And the list goes on.

So, how did this progressive piece of media play with 1930s audiences?

Banned.

Oh, yeah, it was that controversial, with critics expressing shock at the unseemly display of these “others” alongside “normal people” –presumably before sniffing through their moustaches and saying, “Most unorthodox! Most unorthodox! Harumph! Harumph!”

The film ruined Browning’s career. He continued to make movies, but his fame as the great director of Dracula was pretty much nixed. It would be like today’s audiences discovering that David Fincher had made The Human Centipede. Maybe he would still work, but no one would want to give him a budget. Even so, Browning managed to make a few more films, but these were mostly forgotten flicks in the low-budget horror genre. However, his contribution to film history with his two most memorable works has been astounding.

The idea of The Other is a huge theme in horror, and Browning highlighted this as a source of both pathos and terror. In Dracula, Otherness is due to monstrosity, being something outside of society because of one’s own evil nature. In Freaks, Otherness is due to society being the monster, with our heroes placed outside of the world due to how prejudiced everyone else is. These two themes, one of the otherworldly or outsider-by-action villainy, and one of the isolation imposed on Othered characters, are both prominent in the horror genre. Horror does not often teach a straight-forward lesson, but instead it shows audiences what they fear, turning a light on the fears, as it were. In Dracula, audiences confront fears of the unknown, of being vulnerable to evil, and of being consumed by this evil, as victims themselves become vampires.

In Freaks, Otherness is due to society being the monster, with our heroes placed outside of the world due to how prejudiced everyone else is. These two themes, one of the otherworldly or outsider-by-action villainy, and one of the isolation imposed on Othered characters, are both prominent in the horror genre. Horror does not often teach a straight-forward lesson, but instead it shows audiences what they fear, turning a light on the fears, as it were. In Dracula, audiences confront fears of the unknown, of being vulnerable to evil, and of being consumed by this evil, as victims themselves become vampires.

In Freaks, audiences are forced to considered where they stand in society, and whether or not society’s fears are actually what should frighten us. What is more scary? The demonized outsider or the one doing the demonizing? Who is the real monster? What are we so afraid of? (Why aren’t we supposed to end sentences with prepositions?) Both films question whether or not we, the audience, can become villains, either by our treatment of others or by being consumed by an evil. In Freaks the “normative” person is a part of a society that creates monsters. In Dracula, the normal people can become the outsider and monstrous Other through evil forces.

What is more scary? The demonized outsider or the one doing the demonizing? Who is the real monster? What are we so afraid of? (Why aren’t we supposed to end sentences with prepositions?) Both films question whether or not we, the audience, can become villains, either by our treatment of others or by being consumed by an evil. In Freaks the “normative” person is a part of a society that creates monsters. In Dracula, the normal people can become the outsider and monstrous Other through evil forces.

And remember, even if you keep the light on, even if you are under the covers, monsters can still find you.

C.