That isn’t entirely true.There are quite a few dystopian novels I like, a lot. But, I don’t like contemporary dystopias. There, I said it. In fact, with very few exceptions, I don’t like the genre at all. But, with the new Hunger Games knockoff Divergent (quickly followed by two visually cloned dystopian films, The Giver and The Maze Runner), I don’t think it’s going away soon, at least in the movies Hollywood chooses to adapt. (Edit note: As far as publishers are concerned, though, it’s kind of yesterday…)

So, let’s first look back a little at the development of the modern and contemporary dystopian story and where we have this odd, new trend. Because, it is an odd trend. The Mean Girls and 16 Candles of today now feature evil governments and martyr protagonists taking the place of school dances and popular kids. It’s a sociologically interesting trend.

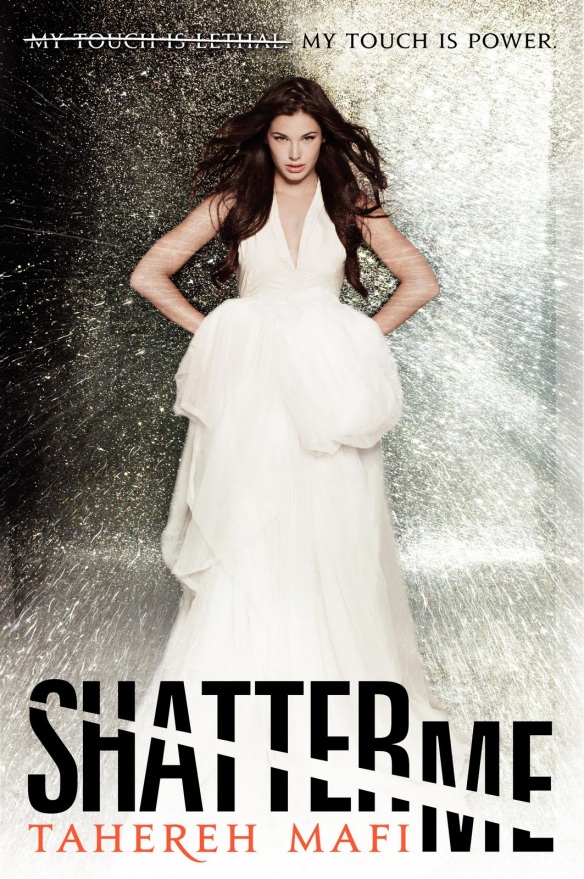

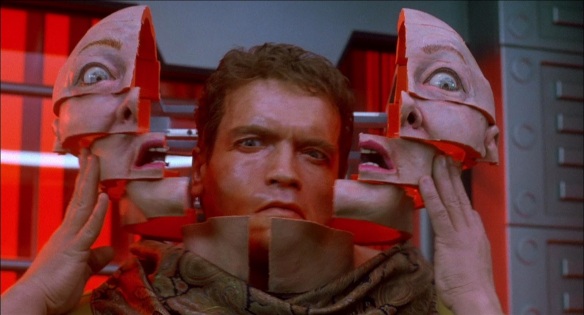

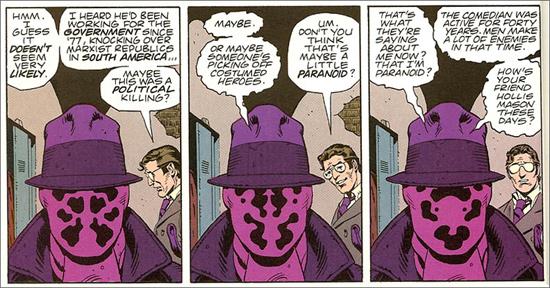

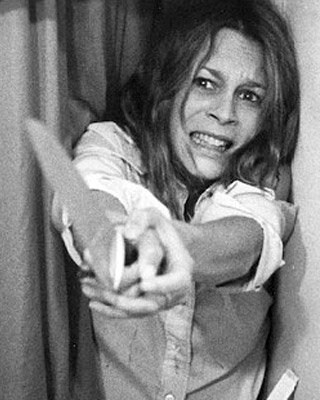

Our stories have gone from this:

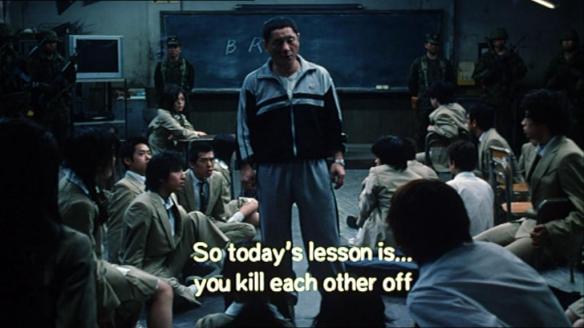

To this:

In many ways, the first real, modern dystopia was We by Zamyatin, a Russian author whose dissenting work made him one of the most banned writers in the USSR.

We is a story about social philosophy. In the USSR, there were artistic and social movements from Russian Constructivism to Taylorism, which deemed that one could create a rational utopia through mathematical harmonies and collectivism. In the novel, the dystopian society thinks and communicates through numbers and mathematical formulas, all while living in a literal protective bubble. The main character, rather like in Orwell’s later work, 1984, briefly has a chance to change his life, through the influences of a woman and the discovery of the outside world. This is the basis for the entire novel. I would not go so far as to say this was a brilliant work of fiction. For one thing, the mathematical aspect of the novel is not entirely realized, since the author was not really a mathematician, and furthermore the technology and speech makes it very dated. There are also some troubling racial politics, as the dystopian society is racially integrated, but the narrator still, for some reason, has to constantly say negative things about the only black person he knows. Classy. And I can’t help but note that integration seems kind of tied to the negative aspects of the collectivist society. However, one cannot deny that this is really the kind, if not the quality, of dystopias that should be written. Zamyatin was writing against a powerful and corrupt government, and used the science fiction story to illustrate concerns he had with the world he lived in. He also risked a great deal to write this book, and it widely banned in his home country. That’s a key that most fans of dystopia forget. Almost all fans and writers take exactly 0 risks these days. I mean, The Hunger Games has a hilariously unironic Subway tie-in deal, so if anything screams that that dystopia isn’t coming true, it’s a Hunger Games meatball sub.

What I am saying is that dystopia does not have its roots in stories about oh-so-special people who are special, and there’s some kind of baddy government or something, and the special people have a love triangle, and bang! Boom! Bang! Exciting!

That really isn’t the history of dystopia. Also… I would not suggest reading that…

Other landmark dystopian classics followed. 1984, which I’m just going to assume almost everyone has read by now, is the quintessential dystopia.

It draws heavily from We, but creates a far more sophisticated world. Orwell’s understanding of language not only provides crisp prose, but also a world where language, as opposed to numbers, is the key. The twisting and distortion of language, through New Speak, is a huge element, almost as popular a concept as the iconic Big Brother Is Watching.

Another landmark text is Huxley’s Brave New World, which, for some reason, is faddish to pit against 1984. Stop me if you’ve heard this before: “Ahem, so, lyk, we thought we would be in 1984, but really we’re, lyk, in Brave New World, because of TV and stuff…”

Yeah…

(By the way, speaking as a non-TV owner, let’s stop bragging about how unplugged we are when we all, yes all of us, binge-watch shows on our computers. True Detective in one sitting, am I right? We aren’t superior to TV viewers. We’re just more efficient…)

It really pains me when literary criticism gets turned into this sort of nonsense. What, did Huxley only write one book? Did Orwell? Are they necessarily at odds? Are there only two dystopian novels worth talking about? What is with this insanity? To make the books an either-or decision, pitted against one another, and to simplify their messages to “1984 has tough gov’ment” and “Brave New World totes choses ur own captivity” is really to lose the value of each novel. Dystopias are, by necessity, abstracts of social concerns, and each address specific concerns within the context of a novel’s structure. Therefore, a concern in 1984, such as the loss of communication through increasingly politicized language, is not at odds with the bread-and-circuses deadening of the senses in Brave New World. Neither are either of these books at odds with the critique of collectivism and constructivism present in We. I have no idea why the so-called literary analysis of dystopia has become, “Pick one, and only one!” but it’s seriously counter-intuitive when discussing a genre that is entirely about different social critiques. It would be best to look at all angles, would it not?

And, it think that kind of, “Pick one angle! Only one!” reading is something that will come back and bite the genre in the butt. People really start arguing about is the baddy in a dystopia, as if one political side is full of heroes and the other is full of google-eyed monsters.

Another noteworthy book is actually from a very different writer than the previous three. This is Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury. Bradbury is a different writer for a number of reasons. For one thing, where Huxley, Orwell, and Zamyatin were intellectuals, approaching abstracted theories through science fiction modes in a rather Dante-esque fashion, Bradbury was a self-taught writer. His sources came from observation, newspaper writing, and his imagination was formed by classic Hollywood genre pictures and pulp fiction. He was a man of dinosaurs, sideshows, spaceships, and his love of literature and the imagination came from his own pursuits and studies.

Here is a quote explaining why I love this man:

“I have never listened to anyone who criticized my taste in space travel, sideshows or gorillas. When this occurs, I pack up my dinosaurs and leave the room.”

Greatest mind ever? Oh, maybe… maybe…

He never went to college. He was not a major political figure. And, he remains one of the best writers of the era. Bradbury’s fiction is often, almost always, interested in imagination, and the way people approach and love books is a huge part of what inspired his work and what he feared in society. Good characters value books, imagination, robotic Poe-themed houses, movie animatronic model dinosaurs, and they value these things even more than life, at times. Imagination, for Bradbury, is something akin to keeping innocence in the world, and the loss of both wonder and fear is a sign of something deeply wrong with society. This theme is most obvious in his dystopia, but many readers forget that it appears in many of his works. In Graveyard for Lunatics, a character’s loss of his beloved movie models is the impetus for his loss of innocence, and the loss of innocence for many others. His love of his art, the creation of worlds, not unlike creating novels, is his connection to life and humanity. In The Marian Chronicles, characters fleeing government censorship build robotic monuments to Poe, and yet the human characters are also destroying the leftover culture of the Martians before them, replacing beautiful, ancient cities with hotdog stands.

Bradbury, perhaps more than anyone else in the genre, placed a primacy on beauty, understanding that it is not simply the freedom to think of a particular ideology or moral, but also to enjoy and appreciate art that can be so very important. So, when he wrote Fahrenheit 451, the story doesn’t just focus on government restriction of thought. The characters burn books, but what replaces the books is given equal attention. The world left behind is not only misguided in thought, but also bereft of meaning. The characters have no real purpose to live and their actions of either violence or passion do not seem to matter. On the other hand, the good characters are willing to risk death and even die in order to maintain meaning.

Bradbury was quoted saying that one does not have to burn books. One only has to get people to stop reading them. I would add, one could replace great books with a sort of thoughtless page-consumption and get the job done just as well. The empty consumption of entertainment is as critiqued as the excision of literature.

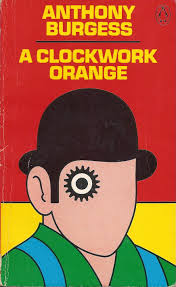

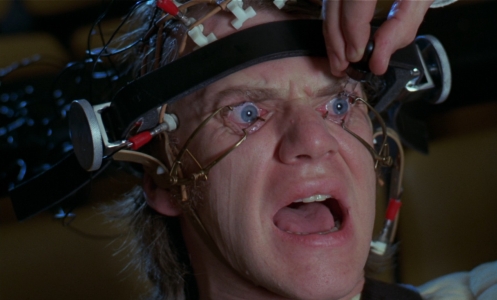

I think that often when talking about dystopias, A Clockwork Orange gets left out. I think a lot of people do not remember that it is actually set in the future, and also a lot of people have a set image of dystopias as Evil Empire vs. The Little Guy. However, this need not be the case, and a true dystopia is merely one which uses political and ideological issues to illustrate a particularly bad future. I say “true dystopia” to differentiate between this and what are really post-apocalyptic stories like The Road or I Am Legend, which are more about survival after the disaster and may not even discuss ideology at all.

Clockwork Orange manages to provide a great deal of detail about the setting without ever telling the reader too much. It’s a corrupt future. Crime is rampant. And, there is a great social disorder, a bankruptcy of morality, a nebulous lack of purpose. The main character spends the first segment of the novel committing acts of violence and maintaining his primacy in his gang. Then, he goes through the infamous Ludovico Treatment and is unable to choose anything but goodness. The novel uses this contrast, a character who only chooses evil being forced to only choose good, to ask questions about free will and morality itself.

And, what I like about this novel, and why it is one of my favorite books of all time, is that it doesn’t make the evil some sort of empire. True, the evil empires in Orwell, Huxley, and Zamyatin do influence the main characters to do evil things, but the evil is clearly stemming from the fact that the characters are under a bad rule. That is the focus of the moral examination, and this is something I do not especially care for in large doses. In Clockwork Orange, Alex, the antihero and narrator, commits acts of horrific violence and depravity, and really just because he enjoys it.He has the same uncomfortable truth we see in The Dark Knight, in the portrayal of The Joker: there is something too human, too entertaining, too understandable in the enjoyment of evil, and that, not scary clown makeup or one false eyelash, is what makes these characters so frightening and so hard to ignore.

Alex takes pleasure in doing wrong, as though it is an art to him. This is illustrated in the way he also loves Beethoven, and how the Ludovico Treatment actually takes from him his ability to feel pleasure in Beethoven’s music. His freedom to do evil is also his freedom to choose beauty. This creates a complex character dilemma, where the reader both sympathizes with and abhors Alex as both demon and victim. And, the evil Alex does, which is truly chilling and disturbed, is not caused because there is a Big Bad Government, but because Alex chooses to be evil. In fact, when the government intervenes, through the morally terrifying treatment itself, it forces Alex to be good. Therein lies the paradox, as it were. Furthermore, if you read the version with the author’s original last chapter, added later on by publishers, you see that Alex’s only real, true cure for evil is boredom. Evil, in the end, becomes tedious, and the sociopathic main character has nothing left to live for.

And that is a very important message! That evil isn’t some exotic, different Other, totally outside of ourselves. It’s not monsters, scary-looking people, political opponents, people who look or live or worship differently than we do. Society has a strange way of othering and glorifying evil. Othering, by making evil something that is not us, even if it means believing conspiracy theories or propaganda. A good example is how every group calls every other group Hitler, and then compares itself to Holocaust victims.

–Also, don’t ever do that.

I cannot tell you how much I love this sort of dystopia, as opposed to the governmental big-bad. This is because instead of giving readers a venue through which they may feel put-upon or victimized, the book forces readers to question their own capacity for right and wrong.

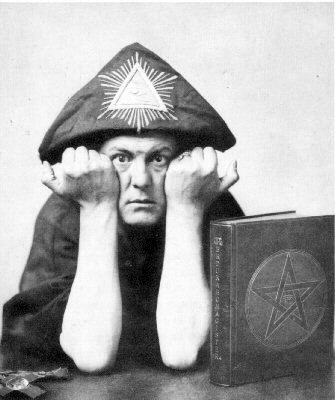

First, a few other mentions in the realm of classic dystopia. One author whose name may not immediately jump to mind is Philip K. Dick. Many people outside of science fiction and online communities do not know this man’s name. And yet, we know his stories, because they have made up a great deal of our pop-culture landscape. Ever see movies like Blade Runner, Total Recall, A Scanner Darkly, and Minority Report? Yeah, these all came from one Mr. Dick, a strange writer who believed that aliens communicated with him. No, really.

Philip K. Dick’s views on science fiction are far more in line with Bradbury’s, if Bradbury thought his Martians were real and was a conspiracy theorist. Although Bradbury is by far the more popular writer in the mainstream, with literary circles fondly embracing him, Dick is actually more successful in Hollywood. And, yet, most people have no idea that these movies are based on books, let alone books by one author.

Probably his most famous work is Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, from which we get the movie Blade Runner. The movie is a rather loose adaptation, but the story is simple. In the future, there are humanoid robots which do work for a civilization that has depleted its natural resources. They, however, are not supposed to be integrated into human society as real people. The line between humans tracking down robots, and robots themselves becomes increasingly blurred. Now, we have seen this before, most notably in the film Metropolis, and the animated remake of the same name.

At first blush, this seems like it may not even fit with the dystopian genre, and would instead be at the most a post-apocalyptic story. However, further reading shows that both the story and Blade Runner are in fact based on an ideological dystopia. Unlike Big Brother and other evil empires, this is about corporations. The story is about consumerism, and through the unbridled corporatism of the setting, humanity becomes commodity and the robotic product is indistinguishable from the human producer. Product and producer are one.

You see this theme again in the sci-fi portion of Cloud Atlas.

Moving back to the evil empires, there is one more angle, that being the evil theocracy.

Margaret Atwood took the formula of 1984 and We and gave it a feminist bent when she wrote The Handmaid’s Tale. This is a story about a future where a dictatorial theocratic society has taken rule, and created a sort of Christian Taliban social policy of female oppression, regressive sexual politics, et cetera. It introduces another category of evil rule into the dystopian complex. In a genre where often the Stalinist themes pits evil empires against religion, Atwood looks at contemporary societal conflicts and creates a religious empire, like a cult that also runs the government.

For the last two landmark examples, I’ll cite two very different writers. One is Orson Scott Card, best known for book and subsequent series Ender’s Game –and also for his controversial politics. The other is Alan Moore, the man who brought the idea of literary graphic novels to the mainstream –and also known for his controversial politics. Card’s Ender series really does not initially seem very dystopian.

It’s futuristic, but the future is one of aliens and spaceships. However, it is what happens on earth, and the backdrop for his story, which is very dystopian and provides his criticism. Focusing on the first book, Ender’s Game is about a third child in a population-controlled future, the downtrodden hero, Ender. Ender is taken from his abusive sociopathic brother and saintly sister and placed in a space-school to learn how to defeat aliens by playing lots of cool video games. It’s actually somewhat better than that sounds. But, the dystopian aspects take the form of the government control itself. When is it okay to commit acts of violence and who may morally be used? Is what they do justifiable? The story also has a parallel plot about the brother and sister taking over the government through the use of what is basically a blog.

I’ll remove any ambiguity. I don’t think Card is a great writer. I think his prose style is basic and his ideas tend not to be very well… thought out. The blogging aspect requires a lot of suspension of disbelief, for one thing. For another, I do think that Card lets his characters get away with making morally indefensible choices based on the fact that they have no idea what they are doing. While that leads to some good questions about the nature of war, I feel like, from a story standpoint, he chose a very safe route for his character. Ender does not know about his major conflict, and so it isn’t a conflict for him. Instead, he has these Harry Potter conflicts of fitting in at special school and being a special boy, none of which is as interesting as the big conflict that the main character never knows is a conflict and therefore is never conflicted about.

It’s like having a story about dropping a nuclear bomb, but making the main character totally oblivious to what is happening. I think the moral could be sustained far more interestingly in a short story than a novel, which leaves us with pages and pages of a character playing strategy games that don’t feel very connected to the actual point of the story. Adventure, ho.

However, I would say that Card is one of the most influential writers in terms of where the genre is today. He gave us a magic boy character. Oh, sure, Ender is actually a genius, not magic, but the archetype is still there. And, more than anything else, this trait will influence the dystopian trends of today. Although the trends of today may just be miming Harry Potter, not Ender, so I don’t really know.

Also, Card is kind of a bigot, but that’s extrinsic to the quality of his work. I just had to address that elephant in the room.

Moore, on the other hand, is far to the left of conservative, Mormon Card. Moore is an anarchist who believes in wizardry. And, when I say anarchist, I neither mean rioter or dork-with-an-A-symbol-hoodie. I mean that Moore is philosophically in-line with Bakunin and Bookchin and Dorothy Day and the band Chumbawama. And, he uses his work to illustrate his politics and philosophy through the pop-art of graphic novels. Does it work? Hell’s yeah! I may like Clockwork Orange best of these novels, but Moore is the writer I have read the most. It’s not just that he managed to seamlessly melt literature and comicbooks into one glorious pop-art entity, like some superhero Warhol. It’s not just that he mixes pop-culture with philosophy. Oh, no, he’s also just kind of brilliant. That’s all. Just a great, great writer with smart, intellectual plots, and memorable characters.

So, what’s so dystopian about Moore? Well, his most obvious and purest dystopia is V for Vendetta, but I would argue that The Watchmen is also a dystopian story. In V, the future is ruled by fascism, and the titular antihero works as a vigilante against the Nazi-esque government. This sounds straightforward, and in lesser hands (like, say, the makers of the V for Vendetta movie, which sucks), it could easily be pretty simplistic and stupid. However, Moore understands perhaps more than anyone else in his medium the idea of moral grays. V fights against a government that is undeniably evil. But, he does so through acts of terrorism, and he quite literally tortures an innocent.

He is chaotic anarchy personified, the first wild blasts against the armor of a dictatorship. The evil empire of the story is also more interesting than the parody of the Bush administration in the movie, although one would be crazy not to realize that it is also a parody of the Thatcher administration. But, more than any specific leadership, the rule is one of fascistic abstraction: limited communication, 1984 style Big Brother, curfews, control of the populace, Nazi-like concentration camps, theocratic corruption, censorship, control of the media. V’s fight can be seen as both a necessary attack on evil, and also a morally ambiguous action of someone who commits atrocity because he has no army. Interestingly, the same may be said for many people called terrorists today, which leads to some very interesting questions about who we root for. Do we root for V’s actions, which can be legitimate terrorism, if we see the trappings of Hitler on the enemy? Furthermore, how much of V’s vendetta is personal, based on his own experience in a concentration camp? The end, with Evey Hammond donning the iconic mask, says that anarchy, as an ideal, will go on, but in the hands of the gentler, the post-revolution proletarian rule.

The Watchmen is also a dystopia, if one doesn’t become too fixated on the superhero aspect. The story parallels actual history, and asks how much freedom are we, as a society, willing to give up for protection. And, after we have protection, who protects us from the protectors. Who watches the Watchmen? That is the central theme of the story, and one which, in a world of government spying and other miscarriages of justice, feels all the more apt.

So, if you can’t tell, I really, really, really love these graphic novels….

Also, Ayn Rand wrote Anthem. So, honourable mention, even if it is by Rand. It’s actually not bad. Like, at all. Even if you hate Rand, it’s a pretty decent retread of the ideas in We. It’s not extremely influential, but it’s a decent, little book.

So, my purpose of outlining these books is to note that dystopia has a rather varied past. Which really begs a very important question: why do they so often sound exactly the same now?

And why, if I love many of these novels, do I kind of dislike the genre as a whole?

Well, first of all, I am going to posit that we, as a reading populace, have sort of forgotten what dystopia means. I don’t just mean writers passing off vague apocalypses as dystopia, just to create an easy baddy for our preternaturally sexy protagonist. I mean that as readers we have forgotten how to read a dystopia. For one thing, dystopias are not prophesy.

They are not predicting the future. They are, instead, focusing on a problem in the era of the author and discussing it through science fiction as a sort of metaphor or analogy. 1984 is analogous to problems in the USSR, for instance. Fahrenheit 451 illustrates the problem with losing books and great thought. But, even beyond this, many issues in dystopian classics are not about a particular power, but about individual problems, problems which readers may even find within themselves. Have we stopped reading great works? How do we judge the actions of others? How to we value freedom? What would we do?

And, I think that the personal aspect of dystopia, the part which makes Alex such a compelling and frightening character in Clockwork Orange, this is the part that has been excised from reading. Instead, dystopia has become the biggest nail-biting, pants-wetting act of hysteria since people realized they could call all their enemies Hitler.

Stop me if you’ve heard this, “So, lyk, my political opposition is like Big Brother! Or, the people I disagree with are like Brave New World! Also, The Hunger Games is going to happen!”

Yeah… isn’t that all-too-familiar? How often to we hear horribly lame excuses like this, “I wanna say [insert extreme racial slur] without ever being questioned ever! Because people might question me or not want to hire me, that’s New Speak! Political Correctness is New Speak! I am entitled to be hired, even if my rampant racism makes me the very opposite of a team player!”

Yeah, yeah, yeah. You’re on the brink of being shot as a First Amendment hero for your brave use of the n-word. Nevermind that even Westboro ding-dong-the-witch-is-dead Baptist has been legally protected as free speech, this status affirmed in 2011, so that the most hateful of speech is legal in the US. Nevermind that you’re not entitled to, say, getting paid piles of cash to say whatever you want to a major TV audience (*cough* Duck Dynasty, you’re not constitutionally entitled to a reality show *cough*). Nevermind all that. Some New Speak law is comin’ ‘round the bend, yo!

Furthermore, what is interesting is how vague dystopias have become and how both sides gleefully use dystopia to say not, “Hey, let’s talk about our problems!” but “OMG, that’s exactly what my political opposition will do!!!! Run for the hills whilst pissing yourself dramatically!”

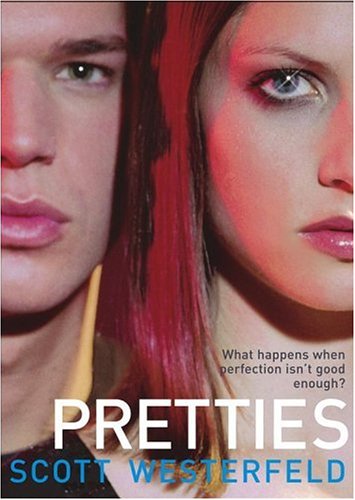

Perhaps there is no greater example of this trend than the way in which people read The Hunger Games. It shouldn’t surprise anyone that The Hunger Games became this popular. It capitalizes on two extremely popular tropes: a magic boy (or, in this case, extremely talented girl) archetype, and the love triangle of teen angst. It’s the natural offspring of Harry Potter and Twilight, two of the biggest publishing trends of the entire history of print. (Wrap your mind around that for a while…)

What many people seem to forget while thinking about which HP character they would want to date and which Hogwarts house they’d like to be in, is that Harry Potter is actually pretty political. The story may be about a magical boy who does magical things in a charmingly magic place (and, I’m not making too much fun, because I actually do like this series). Harry Potter is also about an evil ruler with a racist agenda, classist and racist issues in the wizarding world, the problem of media control, and even government corruption. For a story that started out with a wee orphan boy learning that he is magic and getting a fluffy owl friend, it ends with a huge bloodbath surrounding an anti-racism resistance of young people forming basically vigilante bands.

Thank, JKR… That was… exactly how I wanted to end my kiddie reads session. With horrific slaughter and attempted genocide. Happy reading, kids!

But, again, this kind of ending, and the maturing of the HP audience, mixed with their sudden interest in love triangles and escapist romance, made for the perfect meld for The Hunger Games. We were, as a world, apparently okay with seeing massive child-murder, and were also a little excessively jacked about the young vigilante groups. And political revolution in general.

The political climate has been one of resistance and revolution. Even the conservatives have adopted revolutionary rhetoric. And, we, as a society, were getting really comfortable with being doomsdayers. Religious apocalypses, ecological doom, even facebook all had write-ups about how doomed we were in our doomy doom. And, with a pre-existing template called Battle Royale (which is just better, sorry), it’s really not shocking that the story of a talented main character girl in a dark, scary world of evil would have a love triangle while kicking ass. That’s like the least shocking trend ever.

What is shocking is our lack of sophisticated reading. Both the left and right have had this weird argument about whose enemies are more like the dictatorship in this teen adventure series. What is even worse is how happy these people apparently are in seeing themselves as, well, the victims.

And, here’s where things get stupid. Well, stupid-er. Because we’re already arguing whether or not the right or left are the big baddies in a children’s book series, which is already pretty dumb. But, apparently, some people are actually arguing that The Hunger Games, a teen love-triangle story based on a pre-existing Japanese novel about media violence, is actually going to happen.

And this is really where I start to have a problem with dystopia, as a whole. I am not the first person to point out that our society’s obsession with dystopia is actually pretty narcissistic. Oh, our problems today are just so much worse than ever, ever before? And, really, when confronted with this, many people have told me, Yes. They do believe this. Furthermore, they believe we are either in a secret, unknown dystopia now, or about to go into one, and then they scream about Hitler, because reading history, like reading legislation, is less fun than screaming. Yep, today we’re worse off than the victims of slavery,the Holocaust, the Gulags, the Cultural Revolution, and the Black Plague –combined. Not because we’re suffering. Most of these people are very comfortably situated in a privileged class, because those who aren’t don’t have time to argue about dystopia. No, because something bad is going to happen. In the future.

The trouble with dystopia as a trend is that it really isn’t doing justice to these authors in context, or doing justice to the books themselves, or being literary at all. Dystopia, especially dystopia that allows one to insert themselves as the hero and their political opposition as the enemy, is escapism. We are imagining our own martyrdom and delighting in it.

” You’ve got life on backwards, come here let me flip it, there see, now your past is behind you. What’s say you climb down off the cross use the wood to build a bridge and get over it.” Christopher Titus

We aren’t escaping from reality to enjoy a magical adventure with Harry and buddies, or even a silly romance with sexy vampire boys. We’re escaping to imagine ourselves as heroic martyrs in a world of extreme violence, and to imagine our suffering at the hands of people whose politics we don’t agree with.

The main character is me, the hot boy is my crush, and the bad guys are anyone who didn’t vote for my candidate.

Okay, so that kind of freaks me out.

I don’t really blame the authors, anymore than I blame Burgess and Kubrick for copycat Clockwork Orange crimes, or think that American Psycho is the reason we have spree killings. I think that Collins wanted to write a smart story about the media, and, in fact, the games themselves were inspired by reality shows like American Idol, not by any legislative policy. No, I blame our poor readership, obsessed with escapism, obsessed with characters whose skin they can fill, and unable or unwilling to read more intellectual texts which may put history and culture into some kind of context. It may sound harsh, but I think we read very poorly.

And, I think that this obsession with dystopia has fostered a breeding ground for serious paranoia. Remember how I said I would get back to Card’s politics? Well, he may write fiction, but he also thinks about the possibility of a “satirical” (but totally possible, and Obama is evil) future, where youth police the streets and we live in a dystopia. And, the fact is, when your rationale comes from a reading body that mostly consists of teen books and stories about doom, and not much fact-checking or study, there is no dystopian possibility that seems too insane or remote.

I’m sorry if I’m coming down hard here, but there is a reason. Here’s the thing, if you believe your enemy is evil, is going to make kids fight to the death on TV, is Hitler, is the devil, then you are justified in your mind to do whatever you want to this enemy. After all, you’re a hero. You’re preventing Nazi-1984-Hunger Games-Voldemort! So what if that person is totally innocent NOW. This is NOW. Now is just before the dystopia. In the future, that person will be guilty, so any pre-emptive strike is justified.

And, this is why I like dystopias like Clockwork Orange and sci-fi like Minority Report, and the works of Bradbury and Moore, better than other examples. I don’t like examples where evil is because of a big bad. Even if the stories have subtle dissensions from this, that’s clearly not what readers are getting. This is even worse, to me, when the evil is a specific group that isn’t actually doing this evil. Now, if your group is the Nazis, that makes sense. They did do these horrible things. But, if your group is liberals, conservatives, Christians, Jews, Muslims, gay people, feminists, et cetera, then you run a risk of paving the way for pre-emptive strikes against them. This is why I don’t even like Atwood, despite her acclaim, because I think it breeds bigotry against religious people who haven’t actually done the terrible things in the novel. And I don’t like Michael D. O’Brien’s Children of the Last Days series, because it specifically says that liberal media is covering up for an evil dystopia of left-wing, gay, feminist, Satanic, hippie, Gaia-worshipping Nazis (yeah… he has a lot of axes to grind, I guess…). It’s all based on “what if…?”. I don’t like “what if…?”.

In Burgess’s novel, Alex is our narrator, our guide, and we see the world through his eyes.

We sympathize with Alex, the raping, murdering, thug. We sympathize and this makes us question ourselves, morality, freedom, and the evil that we ourselves could do without choosing to do right. We all have a choice.

Dystopia too often becomes shorthand for lazy political accusations based more on personal feeling and emotional gut-reactions to people and parties we dislike, than it is used for helpful social critique.

We talk a lot about remembering history, almost always in reference to remembering that Hitler was a thing and so therefore Hitler is everyone the speaker dislikes. I say, remember all of history. There’s another scary, bloody era that we might want to recall: The Salem Witch Trials. And, this talk of dystopia and preemptive strikes has far more in common with that than with any heroic rebellion against any teen series baddy.

Remember, the people who killed witches and burned devils and werewolves were also afraid, and trying to protect themselves. But, in the end, they are the ones we remember as the monsters. So, the next time you want to call someone Hitler, ask yourself: Has this person started a genocide and invaded countries, bringing about a World War? If the answer is no, chances are good that this person isn’t Hitler, or a dystopian villain, or a witch.

And chances are, the one you fear is just as scared of you as you are of him.

And in that dreadful place

Those spooky, empty pants and I

were standing face to face!

I yelled for help. I screamed. I shrieked.

I howled. I yowled. I cried,

“OH, SAVE ME FROM THESE PALE

GREEN PANTS WITH NOBODY INSIDE!”

But then a strange thing happened.

Why, those pants began to cry!

Those pants began to tremble.

They were just as scared as I!

I never heard such whimpering

And I began to see

That I was just as strange to them

As they were strange to me!

So…

I put my arm around their waist

And sat right down beside them.

I calmed them down.

Poor empty pants

With nobody inside them.

And now, we meet quite often,

Those empty pants and I,

And we never shake or tremble,

We both smile and we say…”Hi!”

-Dr. Seuss

Literati outrage of the day.

Outlit C